Illustrated by Erin Rommel

March should have been cause for cautious celebration. To mark Endometriosis Awareness Month, MPs were due to launch a wide-ranging inquiry into the impact of the disease and how best to diagnose and treat it.

This was something the 1 in 10 women affected have long been shouting for as a matter of urgency. Then came coronavirus.

It won’t have gone unnoticed that attention has, justifiably, been on the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. This is a generation-defining health and social care challenge of unprecedented proportions, and it is only right that all of our precious NHS and governmental resources be directed towards fighting it.

Last week, the NHS announced that all non-emergency and elective surgeries would be cancelled for 3 months to provide enough hospital beds in preparation for COVID-19. One of these surgeries was the hysterectomy that would help my endometriosis and adenomyosis.

To even mention that those with non-coronavirus related health concerns (particularly non-life-threatening ones) might feel hard-done-by right now seems borderline treasonous. I feel guilty even writing this. But after more than 2 decades fighting crippling monthly pain, I’m upset.

I wonder whether those of us who hoped the gender pain gap would finally be addressed can also allow ourselves a moment of mourning as we return to the back of the healthcare queue?

You see, 20 years after first collapsing during my period, 17 years since being parked on a contraceptive pill and advised to simply put up with the side effects, 5 years after finally being referred to a gynaecologist, after undergoing a 6-month chemical menopause and a disastrous year battling with a Mirena coil, in February I was finally referred for surgery.

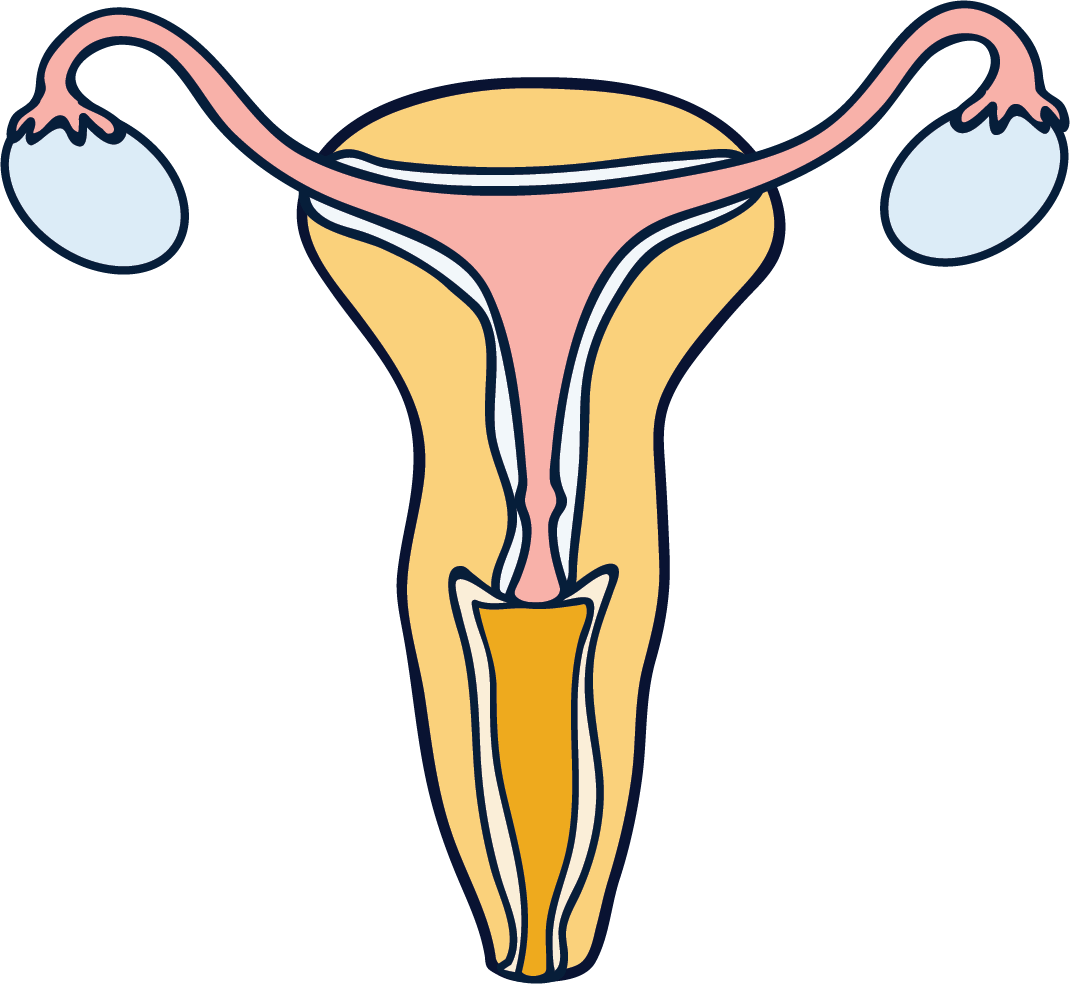

Having been diagnosed with adenomyosis and endometriosis by my doctor, I am now on the waiting list for a hysterectomy. And while that might seem like a drastic decision at 37, I am confident it is the right one for me. I was so relieved at being referred, I wept.

Shortly afterwards, I received a letter telling me that, while the waiting list target is cited as 12 weeks, my health board currently has around a 28-week waiting list. A week after that, all routine surgeries were cancelled in the wake of the rapid pandemic spread of COVID-19.

As such, while I have joined the national outpouring of fear, incredulity and anxiety at our collective predicament, I have also cried over my own reality—that the operation I had so long fought for is now delayed indefinitely, and that I now face not only the same financial and health insecurities as everyone else obeying social-distancing, but also the painful reality of surviving that period with worsening adenomyosis and endometriosis symptoms.

So yesterday I was given an injection to put my body into its second chemically-induced menopause.

Decapeptyl, or GnRH treatment, isn’t for the faint-hearted. The night sweats, emotional turmoil and hot flashes it brings are unbearable for some, the risk of bone loss concerning in the extreme—but for me, it is far better than the unmedicated alternative.

Nevertheless, I am scared. I am scared that I can’t have these jags indefinitely. I am scared that my body will suffer permanent damage.

I am scared about the impact it will have on my relationship, already facing the pressures of home confinement along with so very many others. And I am scared that, with our healthcare system pushed to the brink, I now have no end date in sight.

I am concerned enough that, despite the current crisis, I am seriously considering funding the operation privately by borrowing the £7,000 fee. Even then, I have no guarantee of being seen privately before our fee-paying hospitals are themselves closed down to provide very necessary support to the NHS.

I am also concerned about what all of these considerations say about me as a person. I feel selfish. People are dying—how can I feel upset that I am not allowed to take up a hospital bed? How can I justify my sadness?

While my adenomyosis is not life-threatening, it is very much life-limiting in a way that I think most non-sufferers don’t understand, preventing me from being able to parent my little boy the way I would like to, at a time when parenting feels more important than ever.

These concerns don’t go away, no matter what the bigger picture looks like. They are the concerns that generations of women have yelled about, that have been discarded for too long. And while they now seem less pressing than ever, for those they affect, a life of pain continues, whether in self-isolation or not.

I guess the point I am making is that, while all of us rightfully distance ourselves from others in the name of collective responsibility, spare a thought for those you know who are suffering, your friends and family members whose health concerns continue to plague them at a time when they demand even less attention than usual. They’re still there, and they’ll still be there, suffering, when this is all over.

We can only hope that when we emerge from this crisis, we do so as a kinder, more compassionate society. One that will finally treat everyone’s health concerns, whatever their gender, with the care that they deserve.