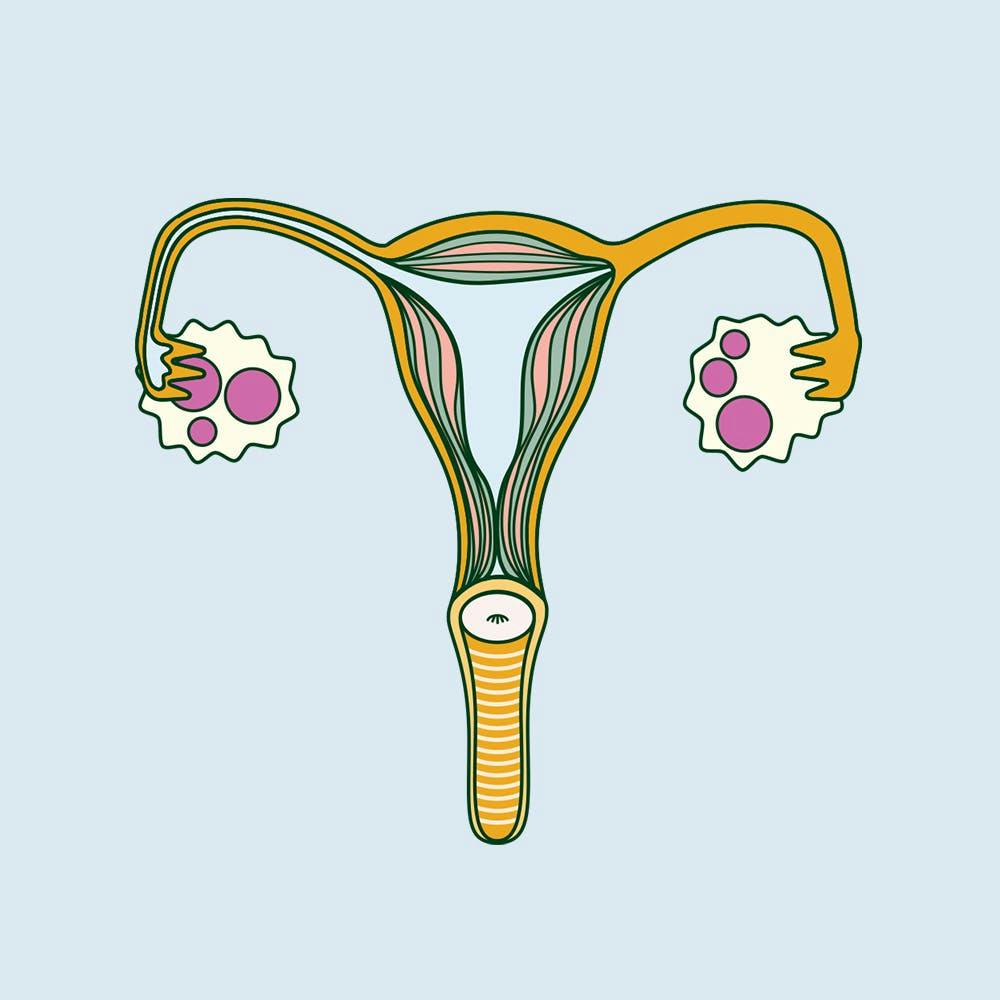

Illustrated by Sabrina Bezerra

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a chronic condition most known for affecting how the ovaries work. The three main features doctors look for when diagnosing are irregular periods, excess androgen (high levels of testosterone or physical signs like excess body hair) and polycystic ovaries. If you have at least two of these features, you are more likely to get diagnosed. However, if you ask anyone with PCOS, they’ll tell you that the condition does a lot more than disrupt ovulation. So, is this really the best way to accurately measure PCOS?

As a period educator and author, I am someone who has a good depth of knowledge about menstruation and conditions that may complicate it. I am also somebody who has struggled with irregular and extremely painful periods all my life. Still, I never for a second considered the possibility I had PCOS. When it comes to diagnosing, typically bloodwork is the first step. They’ll see if your testosterone levels are elevated as well as other hormone levels such as follicle stimulating hormone (FSH). As the latter surges during menstruation, the blood has to be taken at the right point of the cycle - something that many doctors fail to do. When my bloodwork came back normal, I was sent away with no additional help. It wasn’t until I found a new, more competent doctor that I was diagnosed after she tested at the right time and sent me for a follow-up ultrasound. Nearly two years after my initial appointment, my ovaries had enlarged to close to a third of the size they should be.

“

It is such a complex syndrome, there is very limited (and often) incorrect information available to the public, which makes recognising and understanding the symptoms so difficult.

I am not the only one who has had to contend with doctors lacking information; 35 year old and newly diagnosed, Amy told me that her prior knowledge of the condition was dismissed when speaking with her doctor. Her problems were brushed off as other ‘gynaecological issues' but no further investigation was taken. Lauren, who is 30, was encouraged to seek out specialist help after her sister was forced to do the same. As her sister’s doctor ignored her requests for testing for two years on the basis her issues were ‘hormonal’, the pair got their answers from a hormone clinic instead. When asked why so many people struggle to get a timely diagnosis, Dr Tanaya Narendra told me that one of the major reasons is lack of awareness in GPs, general public and media. “It is such a complex syndrome, there is very limited (and often) incorrect information available to the public, which makes recognising and understanding the symptoms so difficult.”

Often when people do get attention, it fails to address the symptoms the patient wants help with. Hannah, who is 28, says: “I’ve not had very much support. My GP said ‘lose weight, go back on the pill and come back when you want to get pregnant’. I felt totally lost. My hormones were all over the place and I was dealing with a body that didn’t feel like mine anymore”. Feeling disconnected from your body is something I can relate to. The truth is PCOS is a condition that impacts me every day of my cycle, not just when I’m bleeding. I experience trouble sleeping and struggle with insulin resistance. People with PCOS can also struggle with chronic fatigue, weight gain, hair loss, inflammation as well as an increased risk of developing health issues later in life such as diabetes and high cholesterol levels — which makes early diagnosis all the more important. As you’re often left to trial and error pain management, diet and supplements in a bid to alleviate your symptoms, it’s a condition that is incredibly hard to deal with without any support.

“

The focus has always been on the ovaries, when we now know that changes in ovarian function are likely a result of PCOS rather than a cause

Many of us who see a doctor about menstrual health will find it is very reproductive centric. Dr Narendra says this is due to “the complex intersections of sexism, patriarchy and regressive attitudes in society at large and also in medicine.” It’s also worth noting that it is hard to undo centuries of medical gaslighting and, in some cases, malpractice. OBGYN Dr Staci Tanouye says: “PCOS has long been associated with decreased fertility given the decreased ovulation and it’s often diagnosed in the reproductive years. The focus has always been on the ovaries, when we now know that changes in ovarian function are likely a result of PCOS rather than a cause.”

Aside from lived experiences, new information is making a compelling case for the rebranding of PCOS. Earlier this year, a study found there may be a male equivalent. Led by Jia Zhu M.D of Boston Children’s Hospital, the study found that men or those without ovaries can develop characteristics of PCOS. Speaking to Healio, Zhu said “by taking genetic factors that contribute to risk for PCOS in women and examining them in men, we found that [they] are associated with increased risk for obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and male-pattern baldness. Thus some of the mechanisms leading to features of PCOS do not act primarily through the ovaries, but rather through pathways present in both women and men.” The more doctors and researchers gain a better understanding of PCOS, the more they seem to be recognising that it’s not just a period issue. “Androgenetic alopecia, which is the early onset of male pattern hair loss, has been shown to have a link with deranged insulin metabolism in the body. Does this mean it is male PCOS? We simply don’t know at this stage. But, it certainly is a curious insight,” says Dr Nerendra. “[As] men lack the regular and elaborate insight into their general health that periods provide for [many], they might go years completely unaware.”

Another study, published in the European Journal of Endocrinology, found that people with PCOS were 51% more likely to get Covid-19 than age-matched people without the syndrome. Even after researchers made statistical adjustments to make sure other chronic conditions weren’t to blame, PCOS patients still had a 28% higher chance of infection. The researchers themselves advised these findings be considered as public health policy evolves, yet those with PCOS were not included in the UK government’s definition of vulnerable groups.

“

In recent years, we have seen many advocates for the renaming of PCOS to Metabolic Reproductive Syndrome in a bid to include all of the symptoms that come with this condition, not just the reproductive issues.

It is clear to see that PCOS is stuck in a longstanding and persistent cycle. The reality of this disorder was not considered enough when it was first described in 1935 by two American gynaecologists. They believed it to be a rare reproductive disorder, a misconception that still overshadows to this day. Many still regard PCOS as a female reproductive issue, when it is a complex metabolic and endocrine disorder. “Thankfully, we are seeing a slow and steady change. Especially as we learn about the hormonal and metabolic manifestations of PCOS,” says Dr Narendra. In recent years, we have seen many advocates for the renaming of PCOS to Metabolic Reproductive Syndrome in a bid to include all of the symptoms that come with this condition, not just the reproductive issues.

With more becoming aware of PCOS and its symptoms, the case for developing research to be considered when treating PCOS grows stronger. We cannot allow traditional ways to hinder progression for patients any longer. There is no denying that PCOS is more than just a lack of ovulation, so what is it going to take for this condition to get a much-needed overhaul?