Table of contents

1. Understanding PMDD: A Complex Condition

2. Living with PMDD: Real Experiences

3. The Path to Diagnosis

4. For Kimberley, it was a long road.

5. Finding Hope and Support

Written by Izzie Price

Medically reviewed by Sarah Montagu (RN DFSRH, BSc)

Illustrated by Maria Papazova

Trigger Warning: This article contains discussion of depression, self-harm, and suicide.

What you'll learn:

- What PMDD is and how it affects daily life

- Real experiences from individuals living with PMDD

- Available treatment options and support systems

- How to seek help and advocate for proper care

Kimberley is 28; and she got her first period when she was 13. She’d always experienced moodiness, irritability and anxiety; but as she reached her 20s, changes in her mood became more pronounced. She’d be depressed for the two weeks prior to her period: “I would become convinced that everyone hated me and that I was useless,” she says.

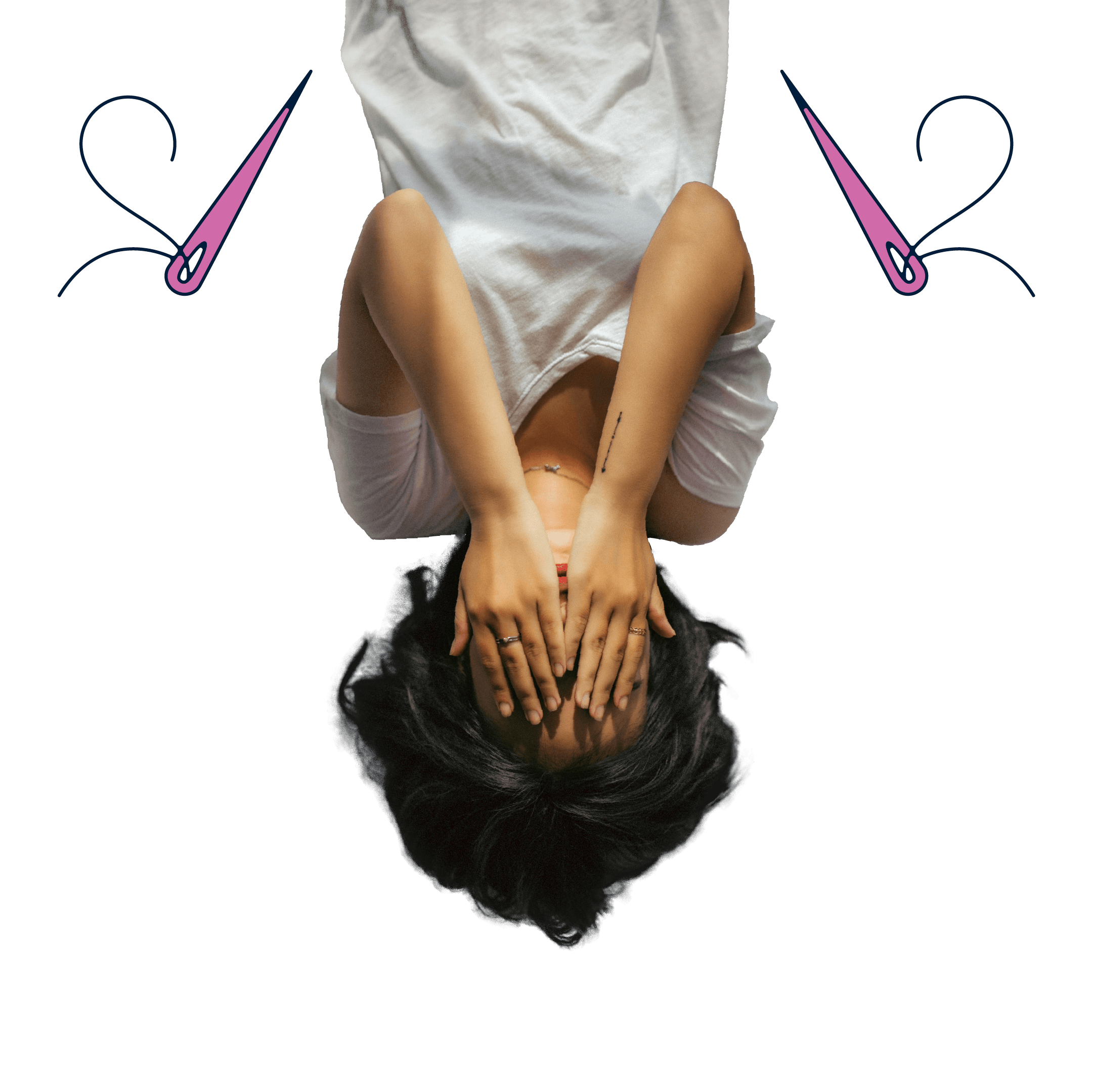

These ongoing negative thoughts would germinate in Kimberley’s brain, creating a feeling almost like physical pressure. “As a form of release I would self-harm, taking a razor blade to my arms and making small cuts. Tending to these wounds would help release that pressure in my head…something that was in my head would become physical and looking at cuts that would ribbon across my arms would distract me and keep me focused,” she says. “I would get [my] period and I’d feel better after a few days. But I always thought it was maybe depression, or something else, as I’d never even heard [of] PMDD.”

Understanding PMDD: A Complex Condition

PMDD stands for premenstrual dysphoric disorder, and is thought to affect between 3 and 8% of people who menstruate.

Physical symptoms include joint pain and breast tenderness, while emotional symptoms include depression, anxiety, difficulty concentrating and suicidal thoughts, among others.

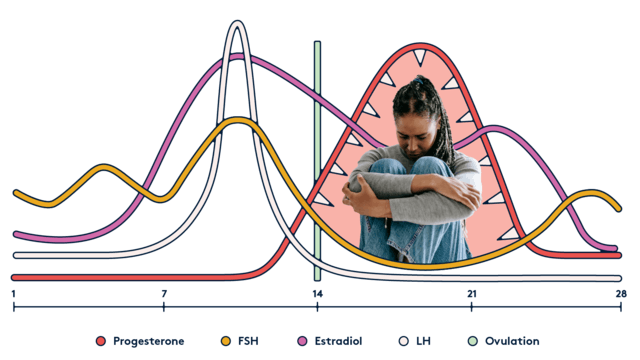

“PMDD is a condition where individuals have distressing emotional and physical symptoms during a specific window of the menstrual cycle,” says Lauren Harrington, MD, FACOG, Assistant Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. “Symptoms of PMDD usually appear in the last week of the menstrual cycle (within a week of the onset of menstrual bleeding) and go away 1-3 days after bleeding has started. Symptoms are then absent for the next 1-2 weeks”. It’s important to note, of course, that this time window will vary with individuals.

Kimberley’s symptoms got particularly bad when she was 24. Ultimately, her [manager] insisted she go to hospital, and she did. “At this point, I was actively having suicidal thoughts and would fantasise about drinking the bleach by the toilet,” she tells me. “I was put into a mental health crisis team to assess my symptoms, and after one tearful appointment, a psychiatrist suggested it could be PMDD. I had no idea what it was.”

“The exact mechanism of PMDD is not yet clearly understood,” says Harrington. “We know that both hormones from the ovaries as well as neurotransmitters in the brain are at play. Throughout the menstrual cycle, the ovaries produce varying levels of estrogen and progesterone and, for reasons we do not yet understand, individuals with PMDD have an exaggerated or pathologic response to these hormone changes.”

Living with PMDD: Real Experiences

Laura Murphy is Director of Education and Awareness at IAPMD, an organisation that offers comprehensive support, information and resources to people suffering from PMDD, together with providing information on other related conditions like premenstrual exacerbation (PME), when premenstrual syndrome (PMS) exacerbates the symptoms of a different condition (such as depression).

Now 43, Laura remembers her own PMDD symptoms starting when she was 17. “I went into a deep depression and, from then on, started suffering from horrific PMS every month, along with bouts of depression and panic attacks,” she says: recalling having to go to bed for around three days before every period during her twenties, “[due to] exhaustion and feeling so down I could not function.

“I was told by doctors that it was ‘just PMS’ and that I needed to ‘learn to deal with it like everyone else’,” she continues. “I blamed myself for being ‘weak’ and spent years feeling very broken.” Laura had the Mirena coil fitted during her 30s, which she says worked well for a while; but ultimately, she “crashed and burnt in a big way”, which resulted in being signed off work for 18 months. “Plus, I started to experience anxiety that I never had before,” she says. “It was only then (through Google!) that I found out about PMDD.”

Kimberley was assessed each day in her initial crisis team – a process that included keeping a diary of symptoms, daily counselling and antidepressants (which made her physically sick). Two months after her first hospital visit – and 11 years after her first period – she was given a diagnosis of PMDD.

The Path to Diagnosis

While the condition may not – yet – be fully understood, it’s vital that anyone who thinks there’s even the slightest chance they might be experiencing PMDD should make an appointment with a healthcare professional right away.

“Your GP will ask specific questions related to symptoms and encourage you to track [these] symptoms throughout your cycle for several months,” says Dr. Hana Patel, a mental health coach and GP. “Then, your GP can consider treatment. You may need to be referred to a gynaecologist or psychiatrist.”

If you are diagnosed with PMDD, it’s important to know that there are treatment options available. “We have several effective treatment options at our disposal for PMDD: antidepressant medication, hormonal medication and cognitive behavioural therapy,” says Harrington. “Some individuals choose to take an antidepressant medication cyclically: [e.g. taking] the medication during the second half of their cycle when symptoms are present.

[Others] find that daily treatment with an antidepressant medication through the whole menstrual cycle leads to better control of their symptoms,” Harrington continued. “Hormone medications are used daily throughout the whole [cycle].”

For Kimberley, it was a long road.

One that included another hospital visit, after which she vowed to take PMDD seriously and to reach an understanding with the condition – but she tells me that things are better, now, and credits new antidepressants (which didn’t make her feel so sick) as being transformational. “I know they may not work for [every]one, but antidepressants gave me my life back,” she says. “[They] take the extremity of emotions away. I don’t think it’ll ever go away completely, but…I don’t have the extreme anger and obsessive thoughts any more; I don’t have the irrational anger and hatred and impatience. I don’t want to kill myself any more, thankfully. And I haven’t self-harmed since 2020.”

Laura, meanwhile, made the difficult decision to work towards having surgery, having tried the available treatment options. It’s the final line of treatment when all else has failed. “[Age] 37, I had a total hysterectomy with ovary removal, putting me into surgical menopause,” she tells me. “By removing the menstrual cycle, you remove the fluctuations that occur every month at ovulation and therefore stop PMDD from occurring.”

“

Sadly, stigma still exists – not just around mental health, but also about hormones and menstruation.

Finding Hope and Support

There is strong community support available, whether in the form of IAMPD, the UK PMDD Support group on Facebook (which Laura used to run) or Vicious Cycle: founded by Laura, it’s a patient-led project committed to raising awareness of PMDD together with improving standards of care.

And when it comes to raising awareness of PMDD in society – in the workplace, for example – Laura is adamant that we shouldn’t need to single out PMDD specifically. She points out that all reproductive and mental health conditions should be understood in order for those suffering to be properly supported.

“It’s a fine line [between educating] people about PMDD and show[ing] just how serious this condition can possibly be – but also show[ing] that many people manage it well and can be real assets in the workplace,” she explains. “Sadly, stigma still exists – not just around mental health, but also about hormones and menstruation.’’ Education is key – and this includes understanding the nuances of the condition. That comes from hearing about lived experiences.

“PMDD is a spectrum condition, and not everyone will have the same symptoms or at the same severity level,” Laura continues.

“For some, reasonable adjustments could be as simple as wearing noise-reducing headphones or flexible working on those difficult days [or] weeks.”

Patel adds that symptoms can also be managed by tracking your cycle, gaining familiarity with your symptoms and practicing self-care. This has been the case for Kimberley, who now knows what adjustments she, personally, needs to make. “When things are especially bad, I just take time off work, get some ready meals in, lie in bed and wait for things to pass,” she says.

“Having the crisis team and their intensive counselling sessions were also useful for me to develop healthy and normal coping mechanisms,” Kimberley adds. “I also try and raise awareness about PMDD wherever I can – I tell friends when it’s going to be a tough week [and] let employers know when I’m being overwhelmed.

“I will always struggle [during] the two weeks before my period, and feel the manic relief when I bleed, but it’s manageable now,” she continues. “I’ve put the support systems in place. I know how to deal with it and to give myself a break. PMDD controlled and dominated my life for over a decade – but when I finally got to know it, understand it and respect it, I’ve not let it ruin anything else for me any more.”

Related Products