Table of contents

1. Why do I have a strong odour down there?

2. What shouldn’t you put in your vagina?

3. What can you put on your private area?

4. What’s good for feminine hygiene?

Illustrated by Sabrina Bezerra, Erin Rommel & Valentin Slavov

Look – we get it. There are still too many vaginal care products that want us to believe our body is dirty and needs to be cleaned out or – shudder – fragranced. The narrative surrounding the vagina as an unhygienic, unappealing area (how many times have you heard period care referred to as ‘sanitary towels’ or ‘feminine hygiene products’?) is all-pervasive.

Not to mention that sneaking fear that too many of us have felt when we smell a distinct odour coming from down there; an odour that can see us whipping out our credit cards and paying whatever we need to pay for a feminine wash to put in the vagina and eliminate that smell.

But we’ve got to leave the vagina well alone. “Vaginal douching [essentially washes that clean the vagina] can increase the risk of STIs, pelvic inflammatory disease and endometriosis,” says Sexual and Reproductive Health Specialist, Dr Deborah Lee.

Vulvas – might – might! – be another story, but we’ll get to that shortly. First, let’s dive into what might be causing that odour; and why intimate cleansers and bubble baths are never the answer.

Why do I have a strong odour down there?

“The most common unpleasant smell from the vagina is [fishy, and that’s] due to bacterial vaginosis (BV),” says Lee, who previously worked with the NHS as Lead Clinician in an integrated Community Sexual Health Service. “This is not a sexually transmitted infection. The healthy vagina contains lots of bacteria called lactobacilli which make lactic acid. These keep the pH of the vagina acidic and ensure the vaginal environment [is] unsuitable for the growth of other bacteria. The normal [vaginal] pH is around 4.5.”

And – somewhat ironically – rather than reaching for a feminine wash as a cure for the odour produced by BV, there’s every chance that said feminine wash could have been the cause. “If [someone] continually washes away the healthy bacteria, by showering and bathing too often, or using products in the vulvovaginal region that kill lactobacilli, this causes a growth of anaerobic bacteria that shouldn’t be there. These anaerobic bacteria produce amines that give BV its fishy smell.”

Lee points out that other odours could be yeasty – “Yeasts such as Candida are quite normally present in the vagina. But if they become active and start to multiply out of control, this is what happens when you have an attack of thrush” –; or metallic during the period stage of your menstrual cycle, as blood contains iron. “Most STIs are asymptomatic,” Lee continues. “Usually, chlamydia and gonorrhoea don’t smell. But trichomonas vaginalis (TV) can cause a fishy smell.”

Regardless, if you’re thinking ‘How do I get rid of the odour down there?’, please don’t try to eliminate it yourself – especially with a perfumed or fragranced feminine wash (again, more on this below). Instead, book an appointment with a medical professional and follow their advice.

And, remember: As one Medical News Today article put it, ‘Although many people may be concerned about vaginal odor and buy into products that claim to eliminate it, it is normal for vaginas to have a unique, musky scent’.

We do understand, though, that – in the words of Cosmo – ‘say you just had sex, finished a workout, or are on your period’, you might feel you want to clean and cleanse the vulvovaginal region. In which case, here’s everything you shouldn’t do (spoiler: Nothing inside)…

What shouldn’t you put in your vagina?

We loved this piece by the National Coalition for Sexual Health, which detailed an approved list of things that can go in your vagina (it included penises, fingers and chemically stable sex toys); but in all seriousness, you should exercise extreme caution.

“The vulvovaginal skin is extremely sensitive,” says Lee. “It’s common for women to have symptoms down below due to a local allergy to hygiene products used in the genital area. Symptoms include soreness, burning, stinging and itching.

“Commercial products [...] contain colourants, fragrances, caking agents and preservatives – any of which can cause a local allergy,” Lee continues. Indeed, the aforementioned Medical News Today article pointed to one 2013 in vitro study which found that ‘Vagisil feminine moisturizer and a spermicide (Nonoxynol-9) quickly stifled the growth of “good” bacteria (Lactobacillus) usually present in the vagina’.

Essentially, the big ‘nos’ when it comes to cleaning the vulvovaginal area are fragranced products (and douching is the biggest 'no' of all). “Women should generally avoid using any perfumed products on their genital regions – this includes bubble bath, shower gel, deodorants, soaps, vaginal douches and vaginal wipes or talcum powder,” Lee confirms. “These products should not be used on the vulva or in the vagina. They are made by manufacturers who want you to buy them, but they are not necessary for hygiene and cause more harm than good.”

It’s not just cleaning, though. “Take care with lubricants as these too often contain perfumes and artificial preservatives,” explains Lee. “Choose a hypoallergenic lubricant, with organic ingredients and one that does not contain harsh chemicals. There is no benefit from using lubricants containing spermicide such as nonoxynol-9 or chlorhexidine.”

But say you do want to clean your vulvovaginal area; how can you clean it and simultaneously keep the clitoris, labia minora and all the other parts of the vulva completely healthy?

What can you put on your private area?

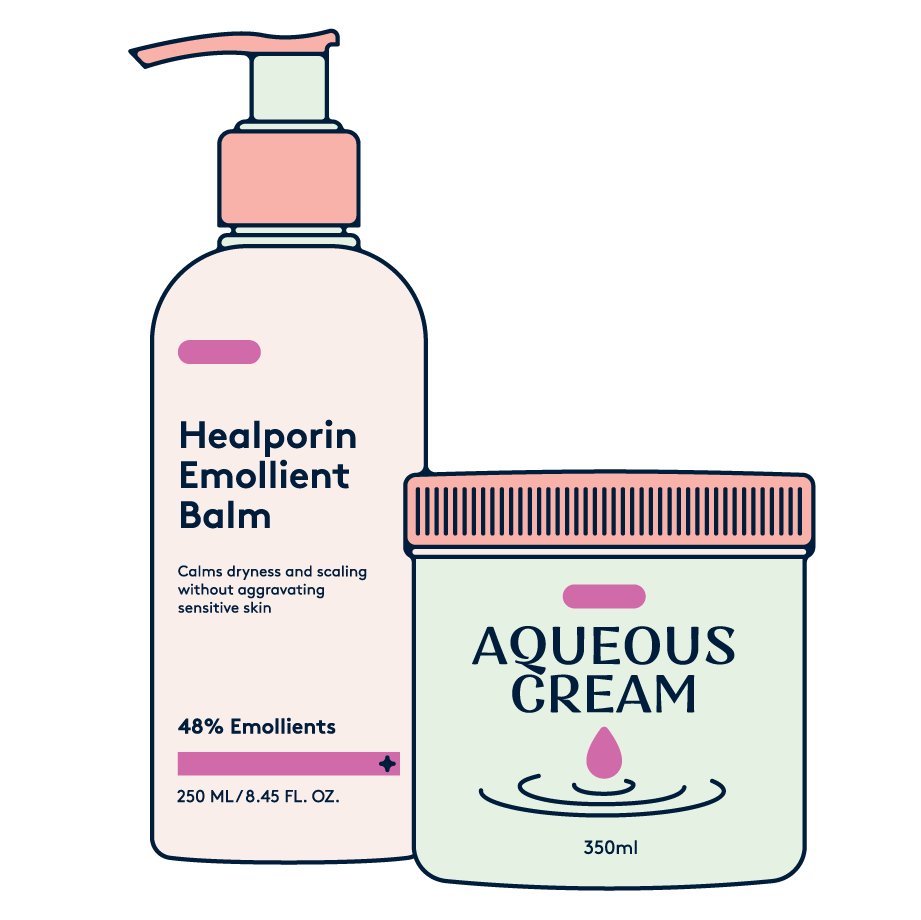

To sum up: Stick to warm water and either Aqueous cream or emollienIf you’re wondering, ‘Is it safe to put water in your vagina?’ – well, the answer is really that the vagina is self-cleaning and you don’t really need to do anything in order to keep it clean and fresh. If you want to help avoid irritation, bacterial infections or vaginal infections, it’s best left alone.

When it comes to the vulva, however, water is ideal. “But don’t add anything to it,” emphasises Lee. “Also, it shouldn’t be too hot, as water removes natural oils from the skin and dries it out, making allergies worse. Wash with tepid [or] warm water, preferably.

And what about soap, we hear you ask? Well, Medical News Today points to a 2017 review that suggested ‘a person should regularly clean the skin of the vulva with mild, unfragranced, soap-free washes to prevent the build-up of sweat, menstrual blood, dead cells and other biological material that could accumulate harmful bacteria.’

Both Medical News Today and Lee reference the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG)’ advice on caring for the vulva. The RCOG says, ‘Using soap substitutes can be soothing and protective [...] Aqueous cream (a special type of moisturiser available without prescription from your pharmacy or on prescription from your doctor) can be used instead of soap’, and points to emollients – moisturising creams and ointments – as another option. Lee echoes this, saying “Water plus emollient only.

“If you feel you need to use a soap, use a hypoallergenic, pH balanced soap – pH 4.2-5.6,” Lee adds.

So, as Cosmo points out, ‘It may be okay to wash your vulva in certain situations when done correctly and with the right, non-irritating product’ – and Cosmo has some suggestions along these lines for anyone wondering ‘what is the best intimate wash in the UK?’; or, indeed, ‘Which product is best for female private parts?’. One such recommendation includes the Dove beauty bar for sensitive skin – ‘an unscented, hypo-allergenic bar soap’ approved by board-certified gynecologist Andrew Roth, MD.

And overall…

What’s good for feminine hygiene?

To sum up: Stick to warm water and either Aqueous cream or emollients for the vulva, and if you must use a soap or wash, go for hypoallergenic, fragrance-free products. Natural ingredients? Great.

General lifestyle advice from the RCOG includes having a shower rather than a bath – ‘but if you do have a bath it is helpful to use an emollient’ – avoiding antiseptics, sponges or flannels to wash the vulva and patting the area dry with a soft towel. The RCOG also advocates trying not to use panty liners or period pads too regularly, and avoiding coloured toilet paper. When it comes to clothing, synthetic underwear is a ‘No’ from the RCOG and loose-fitting cotton or silk underwear is a ‘Yes’; and, finally, try not to use biological washing powders or fabric conditioners if at all possible.

Whenever in doubt, make an appointment with a medical professional at the slightest point of concern. “If you have vulvo-vaginal symptoms, make an appointment at [a] Sexual Health Clinic,” says Lee. “This may very well not be an STI, but they can examine you, test the vaginal pH and do microscopy by examining some of your vaginal secretions. They may be able to make a diagnosis there and then and give you immediate treatment and advice.

“It’s very important that you follow their advice and stop using any perfumed products on the vulvovaginal area,” Lee concludes. “So often, this is the underlying cause of the problem.”

And just one more time for luck: Leave. The. Vagina. Alone.