Illustrated by Erin Rommel & Sabrina Bezerra

From battling cultural expectations for women to remain virgins until marriage to concerns about using tampons, it’s not hard to see why topics on sex and sexual health are shrouded in silence in the Middle East.

Learning about bodies and sex in the Arab world can still be considered taboo. There’s even a dedicated Arabic word for it, “ayb”, leaving many young people with nowhere to turn to for accurate information, whether at home or school.

“There’s a terrible lack of sex education in (both) schools and families,” says Beirut-based Dr. Sandrine Atallah, one of Lebanon’s most high-profile medical sexologists, who is dedicated to spreading sexual awareness. “If people don’t get this, they grow up without knowing they can feel pleasure or that it is their right to feel pleasure or that they should be responsible when using contraception.”

Dr. Atallah says this internalised stigma can have repercussions on sexual health, noting that some female patients even experience vaginismus. “Vaginismus has led to a lot of cases in unconsummated marriages in Lebanon and the diaspora,” she says. Dr. Atallah is also keen to emphasise that stigmas relating to sex and sexual health aren’t strictly a Middle Eastern issue. “These are stigmas that exist everywhere.”

Dr. Shereen El Feki, the author of the seminal book, Sex and the Citadel: Intimate Life in a Changing Arab World, which explores the sex lives of men and women in Egypt and across the region, also stresses that it’s important not to generalise an entire region.

“A young woman in rural Tunisia does not have the same options for access as a young woman living in Zamalek (central Cairo).” Even so, she says that “a lot of material in Arabic ranges from the prurient to the puritanical and finding that middle ground where there’s accessible and accurate information is not easy.”

Sexual health education in the Middle East is progressing

Though the relationship between Middle Eastern women and sexual health has often proved fraught, the landscape is changing. Dr. El Feki attributes this rise to social media facilitating a catalyst of conversations on these issues.

“There are an increasing number of groups really pushing back on the frontiers of what was thought to be acceptable, whether that’s comprehensive sex education or LGBT rights,” she says. “Topics which were thought to be taboo are now definitely on the table, most notably gender-based violence as well as topics such as single motherhood in Morocco.”

A whole host of initiatives have sprung up throughout the Middle East—notable examples include the pioneering Al Hubb Thaqafa, part of Love Matters, which provides online information on reproduction and remains hugely popular across the region, and Muntada Al-Jensaneya, an NGO operating based in Palestine since 2015. The latter was the first online platform in the Arab world that provided information about different aspects of sexuality in Arabic. Dedicated to raising awareness of sexual health in the Palestinian community, Muntanda hosts safe spaces to discuss topics surrounding sexual health and more and involve parents too.

Meanwhile, Marsa Sexual Health Center—a leading sexual health centre in Beirut that promotes access and raises awareness about sexual and reproductive health and rights—has been active on multiple fronts, says a voluntary counselling and testing coordinator at Marsa.

As well as poor sexual education from schools, they say social misconceptions and pressures also take a toll on women. “Middle Eastern women are reluctant to discuss matters related to sexual health for fear of being judged by others. Social pressures…lead them to seek information from unreliable sources.” Marsa’s initiatives include educational workshops on sexual health, prevention, consent targeting women and girls, youth, LGBTQ, refugees and other vulnerable communities.

These sessions are particularly important according to Dr. El Feki, who says that many physicians are very reluctant to talk about sexual health issues because it’s not included in an integrated, comprehensive way in the curricula in most medical schools across the region.

“Marsa exerts significant efforts to change that. We dedicate a considerable part of our voluntary counselling and testing sessions to educating clients on sexually transmitted infections, prevention, condom use and consent among partners,” adds a spokesperson from Marsa.

Equally positive too are the sexual health services catering to the specific health needs of LGBT community in the Middle East.

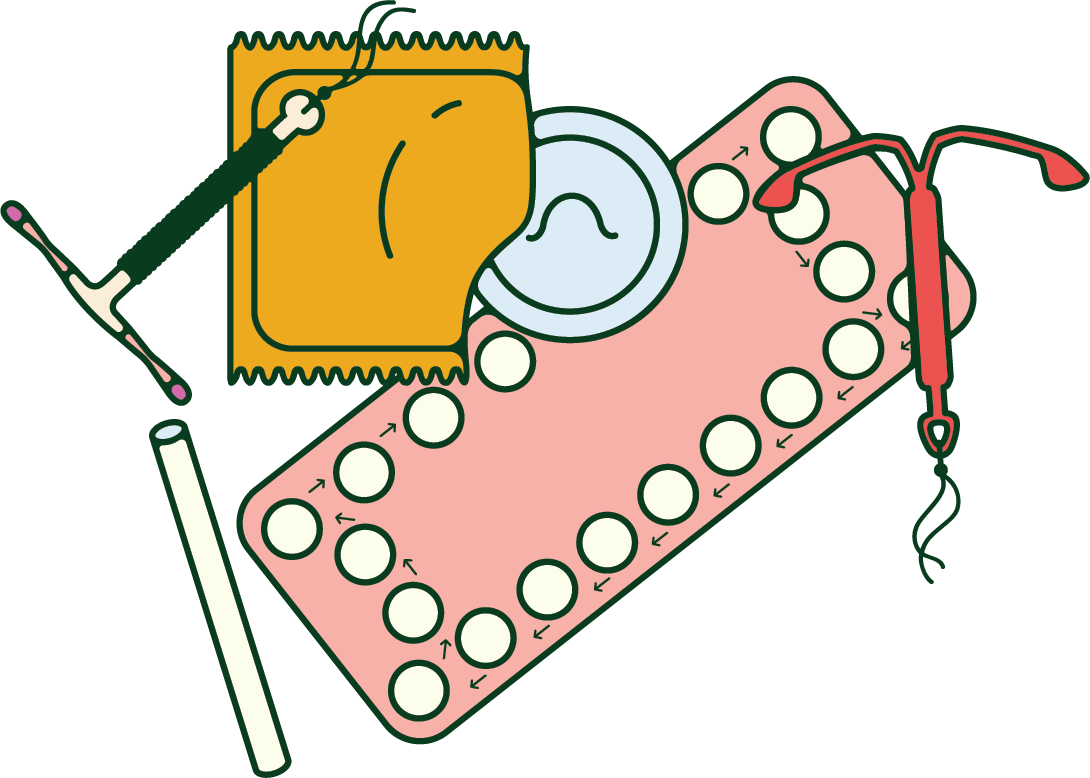

The A Project, a Beirut-based initiative geared towards women and gender non-conforming people in Lebanon features online content ranges from abortion, contraception, emergency contraception and unplanned pregnancies.

It even runs its own daily hotline dedicated to women and the trans community called the Sexuality Hotline, which provides information on sexual and reproductive health including STIs, contraceptive choices including emergency contraception, living with HIV, unplanned pregnancies and disabilities.

In its 2018 report, the hotline recorded a rise in callers from January-December 2018 with 314 callers compared to 166 calls in January-December 2017, with the top 5 topics including contraception, pregnancy scares and issues related to the trans community.

The Marsa Sexual Health Center also launched the trans* project in 2014, the first video campaign of its kind dedicated solely to the trans community in both Lebanon, the Middle East and North Africa region.

These projects are a far cry from what we’ve come to associate with the Middle East. And while plenty of these projects appear to be based in Lebanon—admittedly a country renowned for its progressiveness compared to its Middle Eastern counterparts—it’s clear that these taboos are steadily being eroded. The generational divide is particularly noteworthy too—such services would have been unheard of a decade or two ago, with sex and sexual health education taught mostly within the confines of marriage and from a heterosexual and cis-gender perspective.

As Dr. El Feki says, “These fantastic initiatives are really trying to break barriers in a culturally sensitive way. They’re not just wholesale importing them from outside but are adapting them to the region, carefully pushing the boundaries while taking into account local sensibilities.”

Dr. Atallah, too, has observed a rise in changing attitudes, coupled with a rise in women clients in the last few years. “When I first started in 2007 my practice in Lebanon. I used to see a lot more men than women. Women only used to come for pain problems such as vaginismus. Now it’s different—I see more women searching for their own pleasures and their own satisfaction. Now, sexual wellbeing is more and more important and this is very positive.”

Coronavirus repercussions

Even so, with the advent of coronavirus, the modest gains that have been made in terms of sexual health, and reproductive health access more generally, in the Arab region are now under threat, with services adversely affected.

“Coronavirus poses really huge challenges for sexual and reproductive health and rights,” Dr. El Feki says. “Due to lockdowns, women were not able to access clinics, there were shortages of contraceptives, abortion services—hard to access in most countries at the best of times—were even more difficult to reach.” With government funding priorities shifting to COVID, the future of these services is also at risk.

Another limitation is accessibility issues. Despite a rise in online sites, that doesn’t mean access is for everyone. “(These) don’t help if you’re a Syrian refugee stuck in a refugee camp in Lebanon or if you’re a young woman whose internet access is much more closely supervised and much less freedom to roam the web,” she adds.

Progress in the diaspora

This makes online sites such as Niswa, the sexual health platform for young Arabs both in the region and the diaspora which launched last year, even more crucial in a post-coronavirus world.

Saudi-born, Michigan-based Zainab Alradhi was propelled to create Nisaw after noticing that not one platform has focused entirely on dispelling sexual health myths. “I can’t speak for women in the diaspora but as an Arab who was raised in the Arab world, I can say that sex education is lacking if not non-existent,” Zainab recalls.

“I remember having a class talking about periods but it was only focused on hygiene and religious rules. Those classes only left me with more questions than answers and I craved more information. I recognised a gap in Arabic content…and that sparked a chord.”

Niswa’s topics (which are written in English and translated into Arabic) span contraception, informed consent and sustainability. While Niswa seek to demystify periods and fertility—it explores cycle-syncing and menstrual cups—above all, the platform aims to empower women to take charge of their own bodies.

“Creating a safe space for women to share their experiences is essential to Niswa. We talk about periods, sex, fertility, infertility, pleasure, menstrual products—all which have some degree of a taboo attached to them in the Arab world,” Zainab says.

“Women needed a safe space where they can be themselves, express their experiences and not be judged for it. Women were ready to share and Niswa organically grew into becoming that safe space.” This year, the platform has also offered readers one-to-one sessions and classes, from how to switch to a reusable menstrual product to navigate coming off hormonal contraception.

Crucially though, it’s not just girls within the Arab region that have found solace in Niswa— those from the diaspora too have found a safe space online, whether they’re from Mecca or Manhattan. “Arabic speakers from all around the world have gravitated towards it.”

It’s particularly heartening for Zainab who recalls being told that Arab women weren’t ready, that topics like menstrual cycles were taboo and wouldn’t be received well. “This community formed in the past year are erasing taboos. Since creating Niswa, I’ve learned that despite the distance between us, our experiences are similar and that we are not alone.”

Ultimately though, Zainab believes that it’s critical to provide young women around the world with the necessary tools to feel empowered. “I intend to inspire a new generation of women who fully understand their body, have zero shame about the body and use their knowledge to inform their health and reproductive decisions.”