Table of contents

1. What happened with Allyson Felix?

2. What does the law say: pregnant employees rights

3. Pregnancy discrimination: still a pressing issue

4. The solution: cultural shift in the workplace

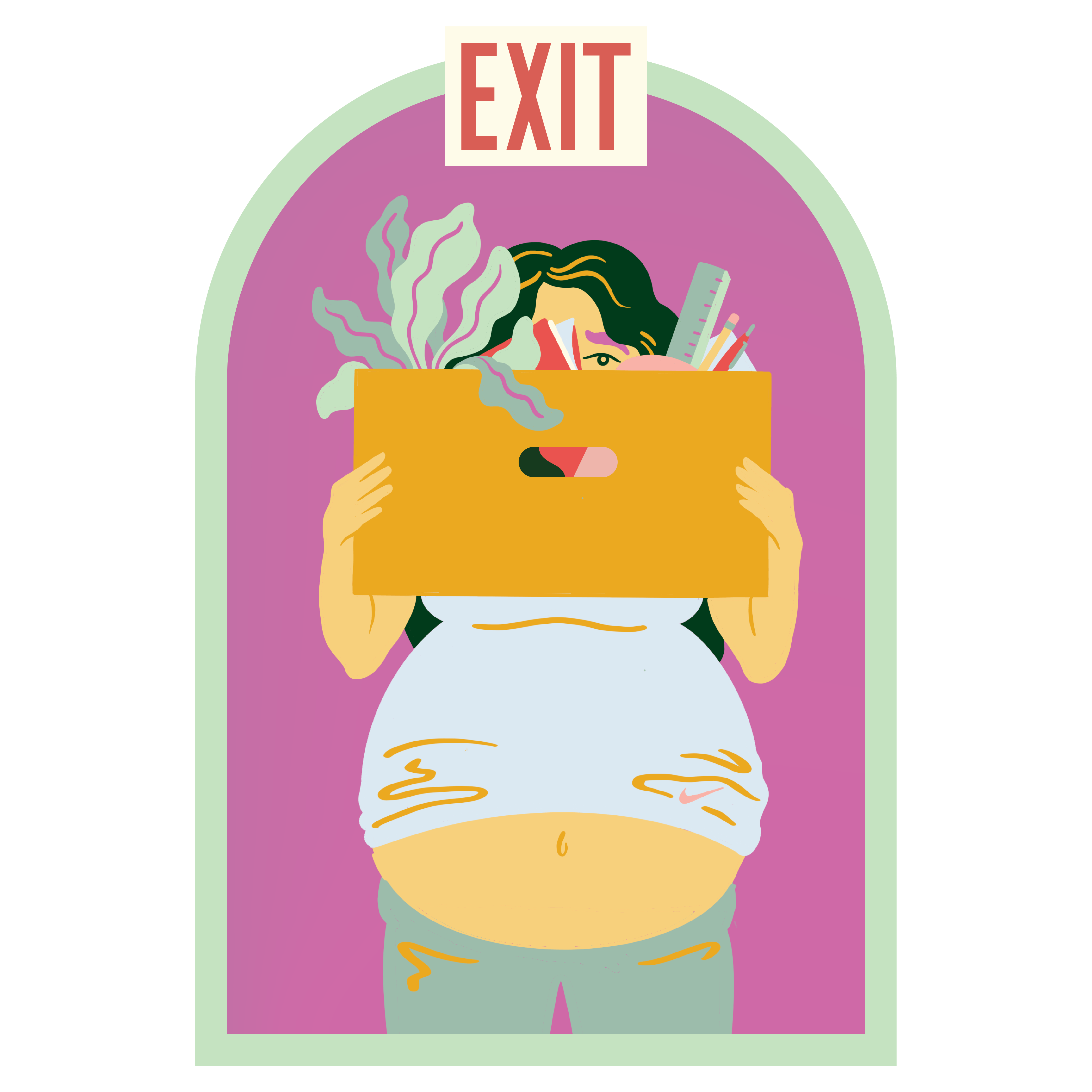

Illustrated by Erin Rommel

What happened with Allyson Felix?

Allyson Felix is the most decorated woman in Olympic track and field history, with 11 medals from five Olympic games. She is also the most decorated athlete in the World Athletics Championship. These are just a few of the many accolades the American track and field athlete has earned in the course of her monumental career. Her decorations and talents led to a long-term sponsorship from Nike.

And yet, when she decided to become a mother, Nike flipped a switch. After Allyson announced her pregnancy, Nike negotiated a 70 percent pay cut for the athlete, in case motherhood affected her future athletic performance. Allyson rejected the new contract. Former Nike endorsers Alysia Montaño and Kara Goucher also spoke out about their pregnancy controversies with the mega sportswear brand.

‘If I, one of Nike’s most widely marketed athletes, couldn’t secure these protections, who could?’ wrote Allyson in a New York Times op-ed.

In the aftermath, Nike changed its maternal policy. But in July 2021, when they reached out to Allyson to feature in a campaign regarding female empowerment, the Olympian hit back once again, calling the brand ‘tone deaf’.

What Allyson and her fellow female athletes experienced were instances of pregnancy discrimination. This can be defined as the unjust or prejudicial treatment of a person due to their pregnancy or maternity. Instances include forcing someone to end their maternity leave prematurely or changing their pay and contract. In other cases, this can mean dismissing the employee entirely.

“

If I, one of Nike’s most widely marketed athletes, couldn’t secure these protections, who could?

What does the law say: pregnant employees rights

According to the UK government, pregnant employees are in possession of four main legal rights: paid time off for antenatal care (such as medical apppointments or parenting classes), maternity leave, maternity allowance, and protection against discrimination. When it comes to the latter, it is against the law to discriminate on the grounds of pregnancy. Under the Equality Act 2010, there is a protected period during pregnancy, which ends two weeks after the end of pregnancy or at the end of maternity leave.

In the United States, the Pregnancy Discrimination Act (PDA) similarly forbids discrimination on the grounds of pregnancy. This applies to any aspect of employment, including hiring, firing, pay, promotions, and fringe benefits.

Pregnancy discrimination: still a pressing issue

Despite the UK’s Equality Act, instances of pregnancy discrimination remain rife. These cases often go uncovered by the media, swept under the rug. The Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC), a watchdog based in the UK, revealed there are still high levels of maternity discrimination within the country. The numbers show this. In 2017-2018, over 1,350 cases of pregnancy discrimination were reported. This is a rise of a whopping 56 percent compared to 2016-2017.

A study by EHRC in 2018 found that one in nine mothers in the UK reported dismissal, compulsory redundancy, or felt they were treated so ‘poorly’ they had to leave work for their own protection. One in five mothers said they experience harassment or negative comments related to their working circumstances from their employer and/or colleagues.

When Vicky Matthews requested a three-day working week after maternity leave, the high-street bank she worked at rejected her request. She was told four days a week was her only option. The request was necessary: Vicky had just had her second child, and her partner – the main wage earner in the house – worked long hours.

“

I had been their golden girl but when I returned from maternity leave, I felt my position within the company was tainted.

‘My opportunities for promotion and recognition were gone, so after the birth of my second child three years later, I took voluntary redundancy.’

‘An even bigger blow came when I was told my current senior management position was not feasible on a part-time basis and that I would need to take on a new, lower, middle management role,’ she says.

Vicky’s experience led her to transition her career entirely, inspired by her inadvertent redundancy. During her time off, she met fellow mother Caroline Gowing at a baby swimming class – and discovered the two of them had similar experiences. From there, Vicky and Caroline set up a nationwide personal assistant service, encouraging flexibility and independence. The business was founded on these principles, allowing young mothers and working mothers (amongst other clients) to continue their career trajectories from the comfort of their homes.

Like Vicky, Beth Davies was essentially demoted after she gave birth to her daughter. Beth worked as a marketing consultant, in a permanent position. When she returned to work after pregnancy, a change in management offered her full-time work at half the pay she was given before. This, to Beth, was a clear ‘demotion’: ‘they didn’t reflect the 15 years of experience that I had,’ she says.

‘They also made it clear there was no room for negotiation,’ Beth explains.

Vicky and Beth are just a few amongst the many mothers in the country who have been treated unfairly due to their pregnancies and pending motherhood. In both cases, demotions and lower wages were readily offered to these new mothers.

Beth also began her own business, which she felt allowed her to work flexibly while still spending time with her daughter. Having her own company let her strike this balance. But it also speaks to a corporate culture in which mothers are less valued than their counterparts.

The solution: cultural shift in the workplace

A YouGov survey, conducted in conjunction with EHRC, looked into employer attitudes when it comes to pregnancy, maternity leave, and pregnancy discrimination. According to the survey, a third of employers interviewed believe that new mothers are ‘generally less interested in career progression’ compared to their fellow colleagues. Over half of employers suggest there is resentment in the workplace towards new mothers taking time off.

The data suggests that there needs to be a major cultural shift in the workplace in order to combat instances of discrimination. Management, in addition to employees, require education about the rights and responsibilities of motherhood. These dialogues and open conversations can help to facilitate a healthier workplace for people who have just given birth.

‘It should be up to the company to value the skills of their workforce enough to see a pregnant woman or mother as much of an asset as they were before they got pregnant or had a child,’ Beth says. ‘Companies are waxing lyrical about employee wellbeing and mental health but this should be as much of a priority.’