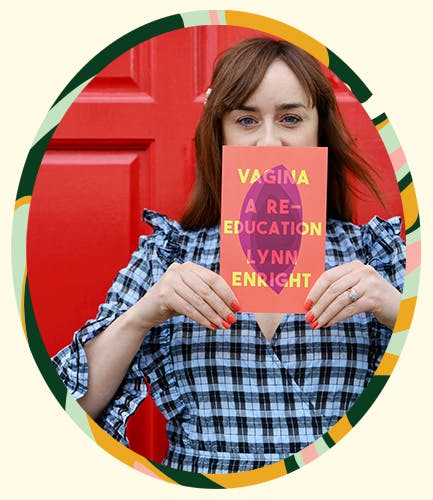

You have been told lies about your vagina. Everyone has. And it’s time to unlearn this misinformation in order to build a more positive relationship with our bodies. So goes the premise of journalist Lynn Enright’s first book, Vagina: A Re-Education.

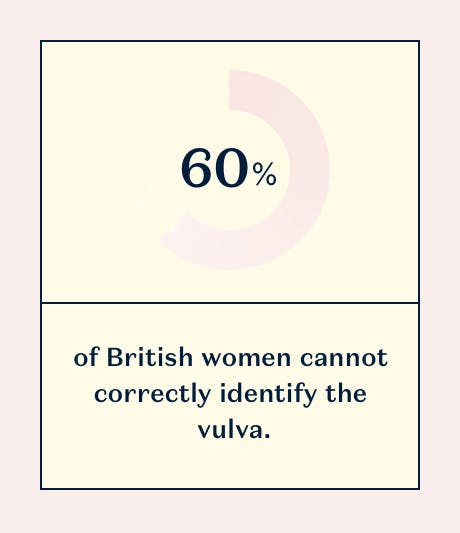

The book’s title is actually a good place to start. In an opening chapter, Enright explains that when we say vagina, we often really mean vulva, the area which encompasses the mons pubis, the clitoris, the labia and vaginal opening. So confused are we about our own anatomy that 60% of British women cannot correctly identify the vulva. “It is a place of vitality, of lust, of life—and yet grown women who have had a vulva their whole lives, feel bewildered by it,” says Enright. Sex education needs a shake-up.

Not knowing our bodies has tangible effects. Enright explains that feelings of trauma often accompany a first period, as “one in seven girls didn’t know what was happening to them when they first began menstruating”. And that’s just the start. There are women who endure painful sex for decades because they don’t know it can feel another way. Women who suffer excruciating pain because of conditions like endometriosis. Enright herself suffers each month because of a uterine fibroid.

She described this horror in her book as a pain that’s almost laughable—“hot and light in my head, as the deep agony pulses through my lower abdomen, spreading to my legs, unsteadying them”—as well as PMS that descends like an “unsettled depression”. She has calculated that over her lifetime she’ll endure over a year and a half’s worth of PMS—and she’s not alone. Why then, she questions, are conversations around things like period care and period leave still shrouded in mystery? “We deny periods, we gloss over periods, we hide periods. We ignore them, suffer through them, tampons stuffed up sleeves and euphemisms deployed.”

What Enright offers in Vagina is a polemic for a greater understanding of female genitalia, by addressing taboos around menstruation, masturbation, miscarriage and menopause. Enright’s book is at heart a rallying cry for women to educate themselves, to ask questions and to demand more from a society which often defines us by our vaginas—and our genders. And also an appeal for more women to share their experiences with other women. “It’s more about being a good listener, not judging and allowing others to open up,” she says. “People will tell you their stories when they feel supported and you can help them heal that way”.

We caught up with Enright to talk all things health, life and vaginas:

In terms of re-educating women, have we been served misinformation about our own bodies?

I think that, sadly, we have. I think that, for the most part, for most of us in the UK or Ireland or the US, our sex education has been poor—at best. And sometimes it’s been downright deliberately misleading.

What are some of the most damaging lies that biological women have been taught about their bodies?

For me personally it related to the hymen. Growing up, I had a troublesome hymen, in that it occluded my vagina almost completely, and I should have been able to talk to a doctor about that but I wasn’t. Sex ed had told me that a hymen was a covering that was broken when sex first occurred so I just assumed my hymen was normal when now, looking back, I realise it wasn’t. But there are so many lies relating to sex, pleasure, pain, fertility, childbirth—I could go on for ever.

What would a positive sex education look like to you?

I think that word “positive” is important. It should feel positive. So many girls leave school terrified of pregnancy and STDs, with an idea that sex is something that boys want and girls need to take responsibility for. Good sex education should acknowledge that sex should be positive and good and pleasurable and fun—for everyone.

Why is a better understanding of female anatomy a feminist issue?

We walk around in these bodies, we live in them and we have sex in them and we work in them. We need to know about them—and we need our medical professionals to know about them too. It’s really disheartening to see how there’s a major gender data gap in terms of medicine and the pharmaceutical industry. Closing that gap should be a priority for all feminists.

You wrote a book about the vagina at a time when there’s a prominent conversation about trans inclusion and questioning of what exactly makes a woman. How did you navigate that?

I care deeply about women with vaginas and about women who don’t have vaginas, as well as people other than women who have vaginas. There is sometimes a sense in our culture than you can only really care about one cause, a sense that causes are competing—and that’s not how I see it. I acknowledge that a lot of this book touches on my own experience and I am a cisgender woman but I speak to people from a lot of different backgrounds. I think if we have these conversations with care and compassion—far away from Twitter!—we can really learn from people.

What are some of your least favourite monikers for the vagina?

Hmm, I think “front bottom” is cute-sounding but so ridiculously inaccurate. The floral ones are obviously the worst, though.

What was the most surprising thing you learned about the vagina while writing? And about women’s relationships with their bodies?

Well, this is about the clitoris, not the vagina—but I had no idea that it extended inside the body! We’ve really been deceived with that one. In terms of other women, I suppose what was interesting was how everyone is so different. People orgasm in such different ways, people experience childbirth in such different ways.

Has your relationship with your own body changed through writing the book?

I definitely know more about it and I think I’m a better advocate for it, particularly at the doctor or when engaging with the medical profession.

How have you taken control of your own health—whether physical or mental? Do you use any holistic supplements or practices?

I do yoga—until recently, that was very occasional but I’m getting better at going frequently. I love it but every time, I forget that until I’m in the room. I’m also I’m a big fan of magnesium supplements—I have a magnesium drink every day.

We see health as having 3 pillars�—physical, mental, soulful—what do you do to nurture each of those pillars on a daily basis?

I don’t always manage that to be honest. But sometimes, I do. Physically, I love it when I look at my phone and it tells me I’ve walked 13,000 steps in a day. I’d like to do that every day but usually it’s more like 9,000. In terms of mental health, I think it’s quite related to physical—if I’m exercising or doing yoga, my breathing will be better and I’ll be more equipped to deal with stress. Soulful health involves cooking for friends, reading and writing, being in nature with my husband—those are the things I look forward to. Again, it’s not daily. Sometimes I’m hungover and stressed with work and order Deliveroo but in an ideal world, that’s how I do best.

You were one of the founding editors of The Pool which recently closed. How have you learned to deal with setbacks and failure?

I wasn’t actually at The Pool when it closed but I was very sad to hear the news. We had all worked so hard on it and then it was gone. I suppose I look for positives in failure: I think it’s always good to take some time to lick your wounds—after a break-up or bad news or redundancy or whatever. Take that time to wallow and be sore and hurt—and then after a few weeks, dust yourself off. There are things that I’ve been through that I thought I couldn’t bear—but I did and I’m here.

Did you feel a particular impetus to write the book being an Irish woman, from a country where abortion has until very recently been illegal?

Yes, absolutely. I think the squeamishness around women’s bodies completely connects to the fact that a necessary medical procedure was illegal for so long. That ban was linked to a disdain for women—and their bodies and sexuality.

What’s your relationship like with your period?

Oof, I hate it. I have a uterine fibroid and I’m waiting to hear if the doctors are going to remove it—it’s been such a long-drawn-out process of me going to the GP then the specialist again and again. In the meantime, my period is an absolute horror.

“I think it’s the worst thing that we do to each other as women, not share the truth about our bodies and how they work, and how they don’t work.” You quote Michelle Obama in the introduction to you book. Do you have any advice on practical questions women can ask other women to get the conversation started?

I think we can try to be honest: about fertility, and miscarriage, and sex, and pain, and anatomy, and pleasure. I’m hopeful. I think women like Michelle Obama have a huge influence and I think lots of women today are much more open with their daughters than their own mothers were. In terms of practical; questions, I think it’s more about being a good listener, not judging and allowing others to open up. People will tell you their stories when they feel supported and you can help them heal that way.