With the midst of fourth-wave feminism, young women protesting for their human rights is now comfortably spoken about.

This is projected on our Instagram Stories, printed on T-shirts, and throughout social discourse as millennial and Gen-Z women navigate unchartered territory when it comes to all things related to our vaginas, periods and intersectional feminism.

But it’s not really all things, is it? Although we have to applaud the work of everyday women that in turn changes the course for all women, we can’t stop talking about the other topics which link to our monthly menses. One of them being female genital mutilation (FGM).

“

Talking about periods can’t simply stop at a lack of access.

FGM seems to be missing from the conversation when we’re speaking about periods or anything related to our vulvas.

Talking about periods can’t simply stop at a lack of access, we also need to dive into what may not be the lived experience all women go through but too many of us encounter.

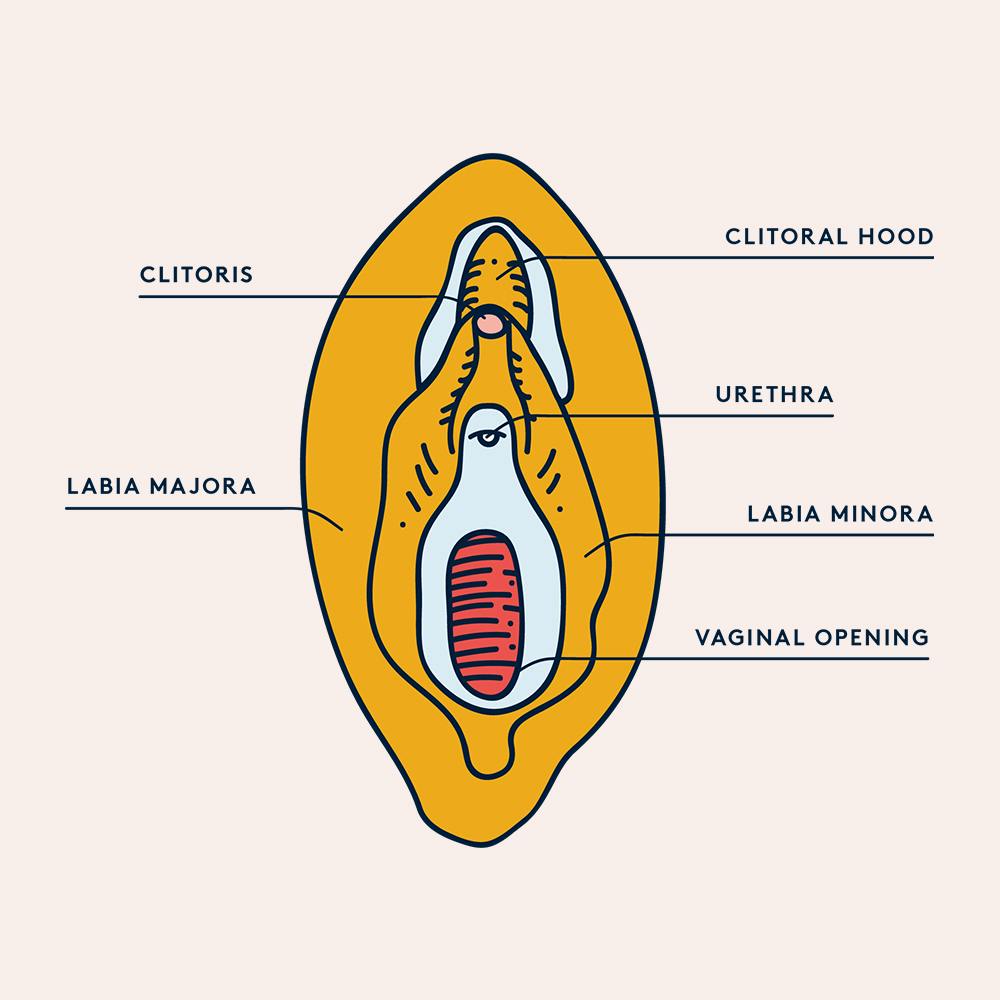

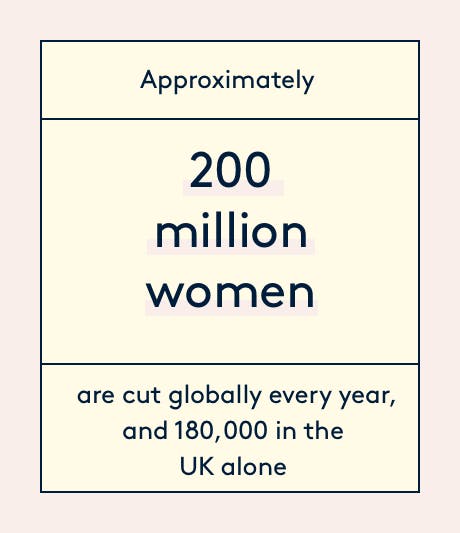

Approximately 200 million girls are cut globally every year, and 180,000 in the UK alone. There are also around 4 different FGM cuts, ranging in how severe the mutilation of the clitoris and labia are.

The voices of young women who experience FGM are still being silenced, so why aren’t we talking more about FGM? Maybe it’s because FGM is usually portrayed as an “African problem”.

Anti-FGM activist Hilary Burrage agrees. “Some people don’t believe it happens here,” she explains. “There are people who say, it’s just a way to keep certain communities down. Which helpfully resonates with the people who are pro-FGM, making it harder for women to speak out.”

But Burrage continues to say that the issue around not speaking about FGM is a complicated and multi-faceted one. One issue is the lack of relatability with women in the UK.

This isn’t a comparison between the struggles of period poverty and FGM—as in many cases they are interlinked—but a key reason why FGM isn’t spoken about widely as cases on period poverty is that with the latter, for example, the majority of women (regardless of race, economical and social background) have experienced a bleed.

FGM is often made out to be a problem for elsewhere, rather than a problem for British women. This taboo ends up hurting the future of young women. “When it comes to FGM, the issue is also how to spot someone who it may happen to soon or has already happened to,” says Burrage.

“We do not have a very diverse police force, who may do its best, but to be able to read things between the lines with FGM, you have to be informed on the dangers of FGM. So there’s a capacity issue within the police force about the lack of cognitive awareness around FGM. We need law enforcement officers from within the community too.”

We also need officers who are able to be open about their cultural backgrounds within the police force, their differences welcome and seen as a positive attribute in stopping FGM.

There is also the issue with trying to be politically correct with marginalised communities who have historically (and still are) overly-policed in the UK. Sometimes the law doesn’t want to get involved in case they seem prejudice and for many communities, the police force is not a symbol of safety, making it difficult for young women of colour to have somewhere to report these issues to.

“

We need law enforcement officers from within the community too.

In her debut title, What We’re Told Not To Talk About (But We’re Going To Anyway), anti-FGM activist Nimko Ali speaks about her and many other women’s experiences with FGM, and how enduring FGM is not when the ordeal ends. “The pain of FGM for me has not really been physical, it is emotional and mental,” says Ali.

The cultural ideals and motivation to act out FGM is behind this belief that it is a way to curb a young woman’s sexual desires. There’s no evidence that this actually works, if anything it just makes other forms of pleasure, even when married (as for many cultures, that’s the only respected time to experience sex) more difficult.

The act of FGM affects young women and how they view their bodies and in turn, see themselves. It tells women their pleasure and joys in life should be silenced and only centre men.

But getting the word out about FGM is not necessarily just reporting it (if survivors of FGM wish for that). Burrage makes the point that in some communities, FGM is not hidden. “The group of women in the UK who have experienced FGM have been largely from Somalian, Kenyan or Nigerian backgrounds but that doesn’t mean that it doesn’t happen to women from all sub-continents.”

“

It tells women their pleasure and joys in life should be silenced and only centre men.

“Generally speaking, in some parts of Africa, FGM is celebrated and done openly. There’s a tradition of having open knowledge about FGM happenings with local girls. However, in places like Iran, Iraq, India or Egypt, people don’t discuss it. Another reason why FGM isn’t being spoken about is that we’re not hearing a wide range of people talk about it.”

The responsibility to be educated about FGM also cannot fall only on women. To report FGM incidents, to know what is happening to young girls and their bodies, and to safeguard children in general must be upheld systemically. “Those that report FGM accounts the most are big brothers of little sisters who sense something is wrong and who are scared their sister may have gotten FGM done to them or are about to experience it,” says Burrage.

“

The responsibility to be educated about FGM also cannot fall only on women.

We also tend to forget that within the United Nations, there are human rights rules for children to have the right to be protected and parents to be afforded the right to honour this safety. Yet with murky Brexit proceedings and pulling out of the EU, that also enlists rules in regards to children’s rights.

There is instability in knowing where laws on children’s sexual education and rights will fall, and the amount of safe places for young women to speak about their bodies is also becoming more restricted, with 30% decrease of nurses in school over the past decade.

So what can we do to keep the conversation around FGM going? Everyone I spoke to for this piece said: keep talking about it. It’s our social and digital power to do so, especially for black and brown women whose voices are not being amplified.

The power behind unnecessary acts like FGM is that it’s built on shame. As FGM is usually decided by mothers upon daughters, having consistent open conversations about FGM and the acts around mutilating women’s bodies in fears of promiscuity, will ensure a change in how unmarried (and largely women of colour) and their desires are perceived to be dangerous and something that must be clipped.

Talking about it starts to chip away the patriarchal hold FGM still has and allows women to take it back, until FGM becomes extinct. Nimko Ali hopes by discussing FGM openly it will save seventy million girls by 2030. By constantly campaigning against FGM, hopefully, the number to save young women from this mutatilation will be more.

.png?ixlib=gatsbyFP&auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=max&w=1637&h=1303)

.png?ixlib=gatsbyFP&auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=max&w=3624&h=2704)